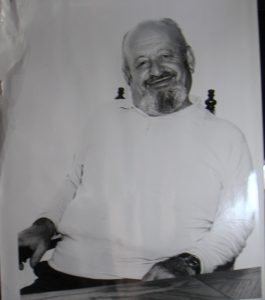

In the picture, my grandfather sits

on a wood chair, leaning back,

the paunch of sixty-three years

preceding him in the foreground

smiling, lip curled

in the narrow space

between mustache and beard

nose sloping downward

olive skin

body compact, heavy.

Add a kefieh to his balding head

and he’s a grandfather of the Nakba,

Arafat’s twin.

But Benjamin Blumin was a Jew—

his own dispersion far-flung and final

nameless forbears fanning out through Europe

to land in shtetls at the gates of Minsk

where he watched Jewish men

get hanged from trees.

His mother disappeared

from consumption, his sister from starvation.

Cornered by catastrophe

he crossed an ocean

to Staten Island.

And there he said the best thing

was he could hit back if assaulted

by a Christian, without going to jail.

The best thing was white bread,

electricity, a hearing aid.

He said the worst thing

was that Black men

could not get jobs

could not hit back if assaulted

by a white.

He braved the ire of the plumbers’ union

hiring Black men, helping them

with licenses, guaranteeing their loans.

This is what catastrophe

taught my grandfather,

what pogroms and malnutrition

led him to do.

This was his small

uprising.

But my grandfather hardly ever

said a word.

Almost deaf since birth, his world

was thick and silent. He spoke

Yiddish and English, but

rarely.

So if we take him, sitting silently

on his wooden chair,

put the kefieh on his head

and move him

from the sands of Florida

to Gaza,

if he never opens his mouth

to let language differentiate

what the complexion of his skin

cannot,

who could he hit back, if assaulted,

without going to jail?

Could he have bread, electricity?

What kind of uprising

would he choose, my grandfather,

if left there

without a job

near a very long fence

stomach empty, unable to hear

waiting for someone

to determine his place?

And who

exactly

would determine

his place?

A number of years ago, I spent a weekend in Washington, D.C. at a conference and lobbying event put on by the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights (USCPR). I roomed with a Palestinian American woman my age, and we stayed up late into the nights comparing notes on our families and upbringings. We were astounded at how similar everything was, the language, traditions, superstitions, familial relations, humor, expressiveness. “Could any two peoples be more similar than ours?” we said.

Michelle Lerner is a second-generation Jewish American living in NJ. She’s a public interest lawyer, poet, fiction writer, and supporter of Palestinian rights.